Use Olshan's Cost-Effective Seawall & Bulkhead Repair System to Seal Cracks & Control Erosion

Restore and protect your bulkhead.

Is the ground around your seawall caving in? Are cracks starting to form? Are joints failing? If you notice voids and sinkholes beginning to appear near your property, it may be time to repair the seawall.

Issues with bulkheads deteriorating are common. Over time, the soil on the land side of the bulkhead will settle for a variety of reasons, leading to the erosion of soils at joints, cracks in panels or below the toe of the bulkhead. Once water finds its way through the bulkhead, the pressure of the water side will pull water through to the land side as water levels rise, eventually pushing it out again as they drop, taking the soil away with it.

The good news is, Olshan offers a cost-effective method to repair bulkheads quickly.

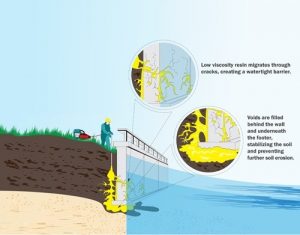

Bulkhead Repair – How it Works

Bulkhead repair is a great way to:

- Fills voids

- Seals cracks

- Stops erosion

- Seals failed joint

The Definitive Guide to Bulkhead & Seawall Repair

Protecting coastal property – overview and how to use this guide.

This guide is a simple, complete and authoritative introduction to bulkheads for coastal property owners in the Texas gulf coast region. It covers all the basics on bulkheads—what they are, how they work and what you should do if you see signs of wear or damage. The guide is organized in easy to follow sections so you can skip around to the topics that apply best to your current situation.

Repairing or replacing bulkheads can be costly. This guide provides valuable tips on extending the life of bulkheads and saving thousands of dollars in preventable construction and remediation costs. If you’re thinking about buying a waterfront home, or if you already own coastal property in the gulf coast region, this guide will help you make informed decisions about protecting your investment.

Read Rudolph A.‘s review of Olshan Foundation Repair on Yelp

Coastal property classifications in Texas

Bulkheads (often referred to as “seawalls” by non-technical people) are the most common form of protection for coastal properties in Texas, but the best coastal defense methods may differ slightly depending on your location. Let’s take a brief look at some of the variations in property types you should ask about before you make any big decisions about bulkhead installation, replacement or repair.

The first and most simple difference between coastal property types is whether they sit on a mainland shoreline, a barrier island, or along some kind of inland waterway. The second big distinction is whether the configuration of the lot occurred naturally, or whether it resulted from human development activity. In developed areas, it’s also important to note how dense the development might be (for example, a single home versus an entire planned community). A third factor to look into is whether your property is situated in an “overwash” area that could be exposed to large amounts of sea water during storm surge conditions. While protection methods might be similar in most of these cases (regardless of design, they all divide water and earth in some way), there may be local code or regulatory considerations that have an impact on the choices you make.

What are bulkheads?

The oldest known seawall was discovered at the site of a 7,000 year-old village on the coast of Israel. It was about 330 feet long and built in a dog leg pattern from boulders that the builders hauled in from a nearby river. It seems that as long as humans have been living next to bodies of water, they’ve been putting up structures to protect their land from waves, tides, and encroaching water. Although some may appear more modern than others, these protective waterfront structures have followed the same basic forms for centuries. Bulkheads are the most common type you’re likely to come across on residential properties in the Texas gulf coast region, but there are a few other variations that serve different purposes.

Retaining walls are generally the most basic form of soil stabilization. These are simple rigid, reinforced structures, usually designed to hold soil at different levels on either side of the wall. Their main purpose is to prevent land movement.

Bulkheads are similar to retaining walls, but contain more engineered components for greater functionality and durability. The biggest difference between bulkheads and common retaining walls is that bulkheads are designed primarily to separate soil from water. The main purpose of a bulkhead is to prevent land movement resulting from erosion, tides, or wave action.

Seawalls are vertical protection structures like bulkheads, and they’re also meant to contain and stabilize the soil behind the wall. Unlike bulkheads, however, seawalls are also designed to withstand sustained wave action and resist or minimize the effects of wave overtopping.

Riprap (also known in some regions as rip rap, rip-rap, rubble, rock armor or shot rock), is artificially placed rock or similar loose materials to reinforce shorelines, streambeds, bridge abutments, pilings and other shoreline structures against water currents, waves, tides or other natural forces leading to soil erosion. Riprap may also be used along the toe of a bulkhead to promote stability.

Revetments are structures used to stabilize soil on a slope. They might consist of random stones or concrete rubble, or they might be built from interlocking geometric materials engineered for that purpose. They usually have an armor layer and a filtration or drainage layer to draw water away from underlying soil. Larger and more complex seawall or bulkhead structures may incorporate some form of intermediate revetment.

How bulkheads work

If you’re just becoming familiar with bulkheads, you might be surprised to learn that they’re not watertight. Their main job is to hold soil in place, not to keep water out. In fact, bulkheads are intentionally designed to let water flow through and away from the soil they’re meant to protect. The goal is to prevent loss of land mass on the protected property that may result from currents, waves and tides, and to maintain proper water depth on the other side for navigation and marine life. Bulkheads also serve to safely mark boundaries between private property and public waterways.

Another important thing to know about bulkheads is that they’re not a single structure. Rather, they’re a system of interlocked components that work together to protect the stability (and long term value) of waterfront property. Here is a quick summary of the main parts of a bulkhead, starting from the bottom up:

Sitting on or just below the natural bottom of the body of water is the “toe” of the bulkhead, reinforced by a “berm” of earth. The berm may be reinforced on the water side with “riprap” to keep the toe of the bulkhead from slipping outward.

Rising from the toe is the “panel” or “slab” material of the bulkhead, which may be made of concrete, vinyl, PVC or a combination of natural and synthetic materials. The panels repeat as needed along the length of the property and interlock by means of overlapping or sealed joints.

Holding the panels in place and in vertical alignment is a series of “soldier piles” or “wall piles” that may be made of wood, steel or reinforced concrete.

Behind the panel on the soil side is engineered “sheathing” or “filter fabric” that serves to keep loose or granular soil from washing through the panels and into the waterway during storm surge, overwash, or runoff.

At the top of the panel, and in back on the soil side, is a 2’ by 2’ drainage trench known as a “French drain.” In some regions, this drainage feature is required by local building codes. The trench is filled with porous material and lined with filter fabric similar to the sheathing on the backs of the panels. The French drain allows water to flow efficiently away from the soil and prevent erosion.

Just below the French drain on the water side of the panel are “weep holes” that are drilled to facilitate efficient drainage away from the protected soil. The weep holes help to prevent the buildup of “hydrostatic pressure” that would otherwise result from collected water.

On the outer (water side) face of the panels are “wales” or “walers” spaced at regular intervals. These are horizontal braces that connect to tie rods for additional stabilization. The tie rods are anchored separately to help keep the bulkhead structure vertical and stable.

Further back on the property and away from the water, “anchor piles” or “deadmen” are placed at an engineered angle and distance. The other ends of the tie rods connected to the wales are anchored here to provide the needed resistance.

Connecting the tops of all the finished panels, a reinforced concrete “cap” is placed to help anchor them together and hold unified structural alignment along the entire length of the bulkhead.

How and why bulkheads fail

From that early pile of 7,000 year-old boulders archeologists found off the coast of Israel, seawall construction methods and materials have improved a lot over the centuries. Still, even with the best technological and regulatory advances, our best experience can’t hold back the forces of nature forever, especially when the power of water is involved. Here are some of the common problems that arise with older bulkheads:

SLAB JOINT (SEAM) SEPARATION: One of the most common causes of bulkhead joint separation is the uneven force of hydrostatic pressure differentials on the panels, especially during low tide. This can also be caused by failure to properly route storm water away from the bulkhead. Joint separation may also be caused by tiedback failure. Typical signs you’ll see include accumulated rock or mounds of sediment on the water side of the affected joint. This is one of the most frequent bulkhead problems that coastal property owners encounter, and there is now new technology to efficiently and inexpensively seal seams and cracks.

TIEBACK FAILURE: Tieback rods can oxidize, corrode and weaken over time. Common signs of tieback failure include a deteriorating cap, cracks or spalling in the concrete at the top of the bulkhead, or settlement of the backfill on the upland side of the wall. In more severe cases, you may notice sagging or wavy panels, indicating that some of your tieback rods may be losing their holding power. In this case, it may be necessary to add new tieback rods and walers to reinforce the weakened areas. Helical tiebacks are sometimes a successful and minimally invasive replacement.

SINKHOLES: These are small areas of sunken earth on the upland side of the bulkhead. Sometimes, sinkhole erosion will happen just below the surface, and the only way you’ll be able to detect this is by the appearance of mounds of earth in the water near the joints of the bulkhead, which may only be visible at low tide. Sinkholes are most likely to happen after a period of heavy rain or unusual overwash events. In this case, it may be possible to correct the problem by cleaning out the weep holes to remove blockage, adding additional drainage paths, or by installing French drains (if they’re not already in place) or by replenishing the filter media in the French drains.

TOE & BERM FAILURE: Over time the cumulative stress from speeding boats or excessive wave action can cause the supporting berm on the water side of the toe of the bulkhead to deteriorate and give way, allowing the toe to slip outward. Signs of berm failure include visible twisting or rotation of the concrete cap, cracks in the concrete, or gaps that open up between the bulkhead and a dock if you have one. Support pilings may also appear tight against the panels, indicating excessive pressure in that part of the structure. In minor cases this may be corrected by building up the berm, adding riprap, or placing bags of dry concrete mix to stabilize the bulkhead again if the toe movement isn’t too severe. In more extreme cases the panels may have to be pulled and reinserted if they’re not too badly damaged.

WATERLINE FAILURE: Long term exposure on the water side of the panels can lead to rust marks and horizontal cracks. As these areas age and expand, the slabs can eventually break along these lines. These kinds of waterline breaks can also occur if the tiebacks are not providing evenly distributed support, and continuous hydrostatic pressure may also cause them to crack and separate. Modern crack repair may be a very effective and inexpensive way to correct this problem if the rest of the bulkhead structure is sound. It’s also very important to ensure that you have proper drainage in place to relieve hydrostatic pressure.

CAP FAILURE: Cap failure is one of the easier bulkhead problems to detect. Obvious symptoms include visible areas of rust, spalling, exposed rebar, and fractures where the cap may be starting to rotate or twist. This can be caused by normal aging of the concrete, uneven hydrostatic pressure weakening parts of the structure, or tieback failure where the cap is having to support more than its designed structural load. The main remedy is full or partial cap replacement, but it’s advisable to look for deeper problems that may be contributing to the cap failure, including berm failure and tieback failure.

Extending bulkhead life

If you don’t already have one, install a French Drain as soon as possible. This will help even out the pressure differential between the land side and the water side of your bulkhead. This pressure differential is one of the most common and most manageable causes of bulkhead failure, and it can become especially severe during low tides and unusual storm activity.

Redirect water from gutters, storm drains or sprinklers so that it does not pool near the bulkhead or run into your French drain.

Keep your bulkhead in mind when you’re planning your landscape and set a 10’ “buffer zone” along the length of the bulkhead. Heavy equipment traveling near the edge of the bulkhead or large trees too close to any of the structural components can cause excessive pressure that will lead to early failure.

Check and replenish the rock or gravel fill material in your French drain frequently and make sure that the weep holes on the outside of the bulkhead remain clean and clear. Weep holes can easily become clogged with sand or soil, which restricts the water flow that prevents hydrostatic pressure buildup.

Have a qualified installer check the perimeter of your bulkhead for potential failure points. Sometimes the installation of supplemental helical tiebacks or extra pilings in strategic spots can help to keep panels in alignment and prevent premature deterioration or failure.

Talk openly with your neighbors and stay active in the community. If everyone follows the local idle speed rules when they’re boating, this protects the berms that hold the toe of your bulkhead in place. It’s also critical for your neighbors to maintain their bulkheads properly and manage stormwater responsibly on adjacent properties. Failures next door can quickly lead to unintended (and expensive) consequences on your property.

Code, regulatory, and environmental considerations

There are some important obligations to consider that go along with waterside living. Keeping them in mind and doing your best to adhere to them will not only help ensure the long-term enjoyment of your property, but also go a long way toward helping you protect your investment and that of your neighbors.

When you purchase waterfront property, you’re also taking on a measure of stewardship for the condition of the water and the creatures that may live there. The choices you make can have a big impact on the well-being of everyone that uses the water, as well as on the wildlife in the region. Here are some tips you and your neighbors can follow to ensure lasting health and enjoyment for all:

- Establish a buffer zone of at least 10’ along the shoreline and keep all fertilizers, pesticides, fuels or chemicals behind that boundary so that they can’t find their way into the water. Be careful to keep these materials off of any paved surfaces where they can be washed inside the buffer zone and over the bulkhead.

- Make sure that stormwater cannot run directly into waterways from your roof, rain gutters, driveways, pool equipment or other drainage systems on your property.Set a policy with your landscaper that lawn clippings, leaves, tree trimmings, compost, or other forms of yard waste are properly disposed of and are not swept or washed into adjacent waterways.

- If you have a dock, never store gas, diesel, oil or chemicals there, on any part of the bulkhead, or anywhere inside the 10’ buffer zone.

- If you own a boat, keep bilges and decks free of all fuels and chemicals in case of automatic bilge pump discharge. To maintain the boat or any personal watercraft, use only biodegradable soaps never household cleaners that can spill into the waterway.

- Talk with your neighbors about waterside practices and work collaboratively with them to make sure that no environmental threats result from use of docks, boats or personal watercraft use or maintenance.

- If you see any unusual spills, colorations, discharges, debris or potential navigation hazards, please notify the appropriate local authorities immediately.

Bulkhead repair considerations

Over time, the soil on the land side of the bulkhead will settle for a variety of reasons. It could result from a number of drainage issues described earlier in this guide or from settlement of the soil against the bulkhead from not being compacted properly at the time of construction. This will lead to erosion of soils at joints, cracks in panels or below the toe of the bulkhead. Once water finds its way through the bulkhead, the pressure of the water side will pull water through to the land side as water levels rise and then pushing it out again as they drop, taking the soil away with it.

- When repairs become necessary, developed lots can present real (and costly) challenges to even the most experienced marine contractors. The presence of houses, trees, landscaping, sprinkler systems, docks, davits, underground utilities, outdoor living spaces and other miscellaneous site improvements (not to mention sensitive structures on neighboring properties) can all present complicated access problems for materials and equipment. The most desirable repair option is to carefully follow all the preventive measures in this guide to extend the useful life of your bulkhead.

- In extreme cases, sections of an older bulkhead may need to be removed and replaced, but this can be very cost prohibitive. Repairs like these can average in the tens of thousands of dollars, but there is a much less expensive (and far less invasive) filling and sealing method that can extends the useful life of most bulkheads for a fraction of what it would cost to replace them. These proprietary materials strengthen bulkheads at the seams and immediately halt soil movement and erosion. This is a very important option for coastal property owners to explore because in many cases the bulkhead is still in good overall structural condition. Professionally sealing a leaky joint can make a lot more sense than tearing it out and replacing it, and there is no excavation needed.

The Olshan Bulkhead Recovery Option

As part of this innovative approach, we often recommend sealing each joint along the entire length of the bulkhead, to ensure that all problem areas are sealed, but we can also address one specific area if needed. Our foam materials react differently than the outdated “fix-all” solution. This means that our products are able to penetrate more deeply into affected areas of the bulkhead, helping to provide a more complete and reliable seal.

When it comes to environmental stewardship, all of our products are NSF/ANSI 61 certified. Meaning they are safe to use on all projects where they may come into contact with water, including drinking water, so they are not harmful to marine life.

How to choose a bulkhead repair expert

- Check out your contractor’s history and credentials.

- Make sure they have the required licenses and insurance coverage.

- Find out how long they’ve been in business and ask for references.

- Contact the references directly and ask about their customer experience.

- Look up their record with the local Better Business Bureau.

- Visit completed jobs and see if you can visit jobs in progress.

- Find out if they offer warranty protection on their work.

- Get a trustworthy estimate of the current condition of your bulkhead.

- Insist on a realistic up-front cost estimate.

- Ask open-ended questions to be sure they’re offering the repair solution that’s right for your individual situation

Terms and definitions

- Anchor Pile (see Deadman):

- Berm: Ground or soil which supports the toe of the bulkhead at the bottom. May also include rip-rap.

- Buffer Zone: 10 foot perimeter to prevent excess pressure on the bulkhead from vehicles, lawn and construction equipment, and landscaping features like large trees.

- Bulkhead: straight wall that separates a body of water from adjacent land

- Cap: Concrete (usually reinforced) box structure which ties seawall together at top.

- Deadman: Poured concrete block approximately 15′ back in the yard which anchors panel and cap structure by means of steel tie-back rod.

- Erosion: Soil from behind the wall escaping into the water. This may occur through defective seawall joints or cracked panels.

- Fill: rock or gravel used to line the interior of a French drain trench to promote water flow away from protected soil.

- Filter Fabric: the porous material that lines the land side of the bulkhead panels and sometimes the interior of the French drain trench. Also called sheathing.

- French Drain: Usually a 2′ by 2′ trench dug out behind the seawall lined with filter fabric and filled with crushed stone.

- Hydrostatic Pressure: Invisible but constant force created from water on the landside of the seawall.

- Overwash area: Overwash occurs when storm waters exceed the elevation of the adjacent land and the ocean water flows onshore. Hazards to onshore development are especially high in overwash areas.

- Panel (or Slab): A reinforced concrete rectangle, 6″ thick and 5′ to 8′ wide and 10′ to 16′ long. These are placed vertically to form the wall. Alternatively, plastic (PVC) sheet piling, composite sheet piling, or metal sheet piling is used for this purpose.

- Piling: Concrete or wood poles placed at regular intervals outside of the panel perimeter in the water to reduce movement of the seawall.

- Replenishing: periodically replacing filter media (rock, etc.) in the fill/French Drain area immediately behind your seawall.

- Revetment: an engineered slope protected by stone, concrete or other mixed materials designed to protect areas of land from wave action and overwash.

- Rip-Rap: Large stone or concrete rubble placed at the toe of a bulkhead to support the berm, stabilize its position and prevent or reduce erosion.

- Seam: the point where wall panels join

- Sheathing: another term for the filter fabric that lines the land side of the bulkhead, and sometimes the interior of a French drain trench.

- Sinkholes: Symptoms: Sinkholes upland of the wall, visible back-fill mounds in the water near seawall joints (most visible at low tide)

- Soldier Pile: A vertical support element, most frequently made of wood or reinforced concrete, that stabilizes the water side of bulkhead panels.

- Spalling: Spalling — sometimes incorrectly called spaulding or spalding — is the result of water entering brick, concrete, or natural stone. It forces the surface to peel, pop out, or flake off. It’s also known as flaking, especially in limestone. Spalling happens in concrete because of moisture in the concrete.

- Tie-Back or Rod: Steel bars connecting the seawall cap and the anchor.

- Waler: A supporting structure installed about 2′ below the seawall top placed on the outside of the panels which normally anchors a separate tie-back rod system to help support the seawall.

- Toe: The bottom of a bulkhead section that sits below the natural bottom of the body of water. The toe is reinforced by a water side berm, which may be supplemented by riprap for extra stability and durability.

- Water Line: normal water level at nominal tidal state

- Water Line Failure: Horizontal cracks in bulkhead panel material caused by rust, corrosion, or other consequences of extended exposure at the nominal water line.

- Water Pressure (also known as Hydrostatic Pressure): pressure differential on the structural components of a bulkhead caused by collected water. Can be corrected with proper drainage measure.

- Wave Action: primary cause of berm failure – natural or speeding boats

- Weep Holes: Drilled holes in seawall above the water line and below the French drain to facilitate drainage and reduce water pressure.

Over time, the soil on the land side of the bulkhead will settle for a variety of reasons. It could result from a number of drainage issues described earlier in this guide or from settlement of the soil against the bulkhead from not being compacted properly at the time of construction. This will lead to erosion of soils at joints, cracks in panels or below the toe of the bulkhead. Once water finds its way through the bulkhead, the pressure of the water side will pull water through to the land side as water levels rise and then pushing it out again as they drop, taking the soil away with it.

Over time, the soil on the land side of the bulkhead will settle for a variety of reasons. It could result from a number of drainage issues described earlier in this guide or from settlement of the soil against the bulkhead from not being compacted properly at the time of construction. This will lead to erosion of soils at joints, cracks in panels or below the toe of the bulkhead. Once water finds its way through the bulkhead, the pressure of the water side will pull water through to the land side as water levels rise and then pushing it out again as they drop, taking the soil away with it.